I didn’t actually see him but I sensed him: a dark, doubtful character desperate for me to understand him. I always see these people as a photographic negative

An intended quick visit to 1485 left me trapped there for 13 months – but I now know it was worth it

The Ashby de la Zouch Canal is, for the most part, a very beautiful part of the world. The first five miles after you’ve navigated the steep east turn off the Coventry Canal is a bit flat, although not without its charm. Things soon get much, much better.

I wasn’t going to take the turn, but a sudden inspiration hit me – something to do with Richard III was somewhere along there, and it might be interesting. I’m not sure I even remembered it was the site of his death until I Googled later on in the day.

Richard was 14th and last Plantagenet king of England, bringing his house’s 331 years of rule to an end during the Battle of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. He’d ruled for 26 months as the Wars of the Roses continued, and he was the last English monarch to die in battle.

Most people know a little about the controversy that followed, especially once William Shakespeare got involved. Richard is accused of many things, although there’s almost no evidence for any of it. It’s considered more and more likely he was the victim of medieval spin-doctoring, and he was a far more successful and popular king than the winners who wrote history have recorded.

That’s the ‘what,’ ‘where’ and ‘why’ – now we come to the ‘who’ – which led to the demanding and exhausting creation of The Gilded Silver Boar…

The area of the canal known as Duck Bend just outside Stoke Golding is right beside the battlefield; had the land contours been different, it might have cut right through it. It’s difficult to imagine the land without the canal, which has itself been there since the 1790s; but that’s still two centuries after the fight took place.

For many years experts felt that folk memory, which placed the battle there, was wrong. By the time it turned out to be true, the visitor centre had already been built in the wrong place. Since the field is private land, only a certain amount of archaeology has been done there – but in 2009, when the Bosworth Boar was found, and more evidence of battle followed, it’s now certain that the battle took place near Duck Bend, overlooked by Stoke Golding to the south and Dadlington to the north-east.

The Dog & Hedgehog Inn was the perfect place to drink ’n’ think (one of my greatest pleasures) – from there I could look down on where the action took place 538 years ago, and consider the situation as the pints came and went. As Meat Loaf has observed, “Some days it don’t come easy / and some days it don’t come hard / some days it don’t come at all and these are the days that never end.” It’s not that desperate, but I find it to be true. I had to wait for inspiration; but in the beautiful wild lands and friendly pubs of these two villages, there was nothing else making demands on my time.

It eventually happened one overcast afternoon (which was unusual – the weather was mainly great during my stay on the Ashby). I didn’t actually see him, per se; but I sensed him: a dark, doubtful character standing not far into the field on the other side of the canal, desperate for me to understand him. I’m comfortable with people thinking that’s weird; I don’t care. I enjoy it! I’m happy if it’s a real proper ghost and I’m happy if I invented the whole thing myself.

(Interestingly, when I see these people I’m going to write about – or for – I always see them in something of a photographic negative style; there’s something inverted about their appearance.)

While he explained himself to me in a series of wordless visions, the one thing I became concerned about was how I could work out his meaning from so far away – about 400 metres, I think. How could I read his expression, and see the look in his eyes? That was ruining the moment for me.

A couple of days later I cruised along to the Bosworth Battlefield Heritage Centre, about 3km from the battlefield itself. I can’t recommend the place enough: inspiring, thought-provoking, beautifully presented for people of all ages, and staffed by bright, cheery, welcoming people. More then worth a visit – and your ticket lasts a year.

As I was leaving I saw the Bosworth Boar itself… and I have to admit I was underwhelmed. It’s tiny – 29mm long – and I totally understand why it was difficult to present it any more dynamically. I took a quick snap of it, just to log my presence, then went on to spend a silly amount of money in the tourist shop, becuase it was a few days before my birthday so I deserved it.

It was only later that I thought: the badge is broken. My first reaction was to imagine an embarrassed archeologist, accidentally smashing it as it was recovered, and hiding the foreleg section from their colleagues, carrying the shame and guilt to this very day. That made me laugh! Then I thought… why is it broken? And does it have any connection to how the character in the field was able to transmit his meaning to me?

And that’s where it really began to take form. The guy in the field carried the guilt and embarrassment I’d imagined for the archeologist. He needed to explain himself and get rid of the weight he’d carried. And he could communicate with me because he’d used some other form of signalling than close-up conversation… and that kind of long-distance signalling was something to do with why the badge was broken.

With all that loaded into the “story engine” at the back of my mind, the conscious part of me could take a break – and I did, enjoying a wonderful cruise to the top end of the Ashby, enjoying the amazing welcome at the Rising Sun at Shackerstone, then heading back to Duck Bend for a second visit.

I’m an early riser – I like to get whatever work I have done and dusted so I can have a little snooze then take the second part of the day to myself and whatever I’m thinking about. I had no work that summer, so I was able to take advantage of some stunning dawn wanderings. I happened to meet the farmer who owns the actual battlefield, on the occasion of his regular cow inoculation day, which he wasn’t looking forward to because the cows knew what was going on and were nervous. That image of the field being full of anxiety gave me an insight into the morning of the battle.

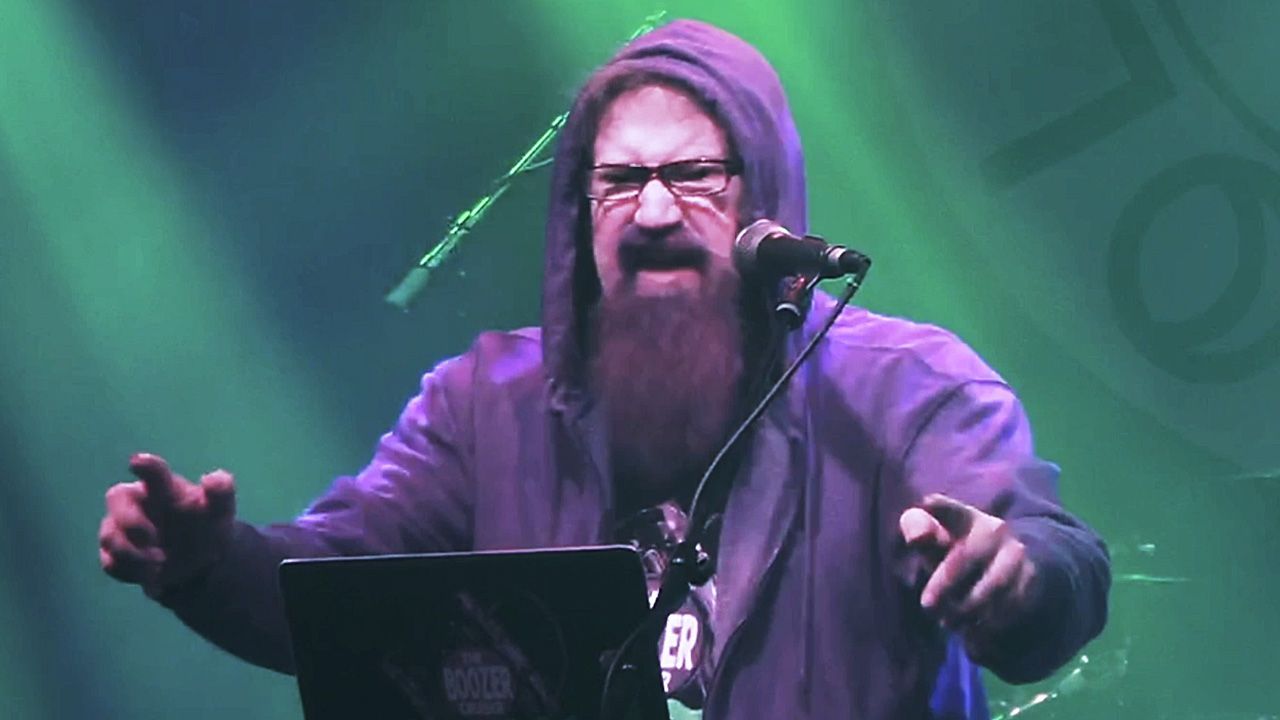

I can feel it as if I’m about to be sick… it’s coming out, soon… Later that day I took myself back to the Dog & Hedgehog and waited. Sure enough, on another overcast evening, He appeared out there down the hill. Within about two hours almost every word of his story was stored in my phone. And it was damn good too – like a lot of people admit to feeling, I’m not sure I wrote it; I may have just been its conductor. But I don’t care because it was amazing to be part of.

From there, it took a long time to refine the story. Long after I’d left the Ashby and my friends at the Lime Kilns Inn near Burbage behind (now under new managament), and long after the English midlands were behind me, I was still engaged in polishing and tidying the most tiny elements. It took 13 months to bring it to YouTube, although much of that time was trying to make my vision for the video into reality with badly-designed software that left me more than frustrated for weeks on end.

The thing is, that guy stayed with me all those months… I suppose in some way since I’d created him or at least given him a voice, he was my responsibility until I delivered. As a result it was not an easy winter: heavy rain and high winds kept me a prisoner on the boat for much of the season, and being alone with his sense of guilt and doubt – while not being aware of it – added to the negativity.

I do suffer from a bit of seasonal affective disorder, but it’s almost like I was dealing with two dozes. I’m glad to say I don’t remember much of that time, except for the family welcome at the Plough in Galgate. Without those guys, I’m not kidding, the winter might have been literally intolerable.

Things started to lighten after I’d tracked a rough demo of the vocal, and sent it to me old mate Andy Glass (of the eminent prog band Solstice) to see what he thought. He played it to his son, Laurie, who expressed an interest in writing a soundtrack for the piece. Once I’d heard his first four-minute demo, it was like the sun came out. Not only was I beginning to get the spin doctor out of my head – I was beginning to feel it would be an artistically satisfying experience. On top of that, I was now sharing the weight of two consciences, which made the carrying (and carrying on) much easier.

Laurie Glass’ astounding soundtrack is the icing on this 15th-century cake. I feel he’s captured an energy both of the era and of the character; and somehow – because we didn’t discuss it – he also captured the playfulness I wanted to illustrate in making a very big story seem like a very small one, and sometimes vice-versa.

I’m glad The Gilded Silver Boar is done, and I’m glad I did it. But it wasn’t easy living with the character’s guilt for over a year. I could really have done without that; it affected my real life in ways I’ll never understand, but sometimes sense. And anyway, we never really discover if he’s genuinely sorry over what he did, or whether he just wants to recruit us for another of his dodgy doctorings.

And I’m not joking when I say that if the only good thing that’s come out of it is Laurie’s evocative composition, then it was all worth it. As a bonus, though, more than that has come out of it – as the future will tell…

I’d like to note two additional elements that make me proud… one, that while Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter – five pairs of syllables with the second of each pair carrying emphasis – I added an eleventh syllable at the end of each line in a sort of triple form with the final pair (sometimes known as a femenine ending), just so my guy was one better than Shakespeare… who he may be referring to in his last line of speech: While history will never know my name / and those who follow me will take the blame.

And two, that while no one has ever been able to offer a convincing explanation as to why the Dog & Hedgehog Inn was named such, I can: Henry VII, who won the battle, took a hound as his emblem, while Richard took (of course) a boar. Richard was in his time referred to by enemies as “hedgehog,” being a diminutive of boar; so it’s no big leap to consider calling Henry a “dog” instead of a hound. I propose, then, that the inn was named for all the working people who had to get on with their lives while games of thrones rolled around them, left a giant mess, and rolled away again for ever.

Sadly the inn is now closed, so Bill, the retired owner, will never hear of my rather clever theory. I don’t think he’d have liked it anyway!